👴 Dynamic Lane Selection

Introduction

For each entity (e.g. vehicles, pedestrians) that needs to get to a specific destination building the base game utilizes a (mostly) static path-finding algorithm in order to find appropriate routes. While TM:PE's Advanced Vehicle AI modifies the cost calculation scheme of the path-finding algorithm in order to create paths that take the current traffic situation into account, resulting routes are still of static nature. They are not only comprised of road segments that shall be used but also predetermine which individual lanes will be taken at a specific moment.

Traffic is inherently dynamic. Several minutes may pass between path calculation and the time when a vehicle arrives at a given lane. At that moment former decisions on which lane to take may already have got outdated. Dynamic Lane Selection (DLS) tackles this problem by introducing real-time adaptions for paths that are calculated by the Advanced Vehicle AI.

Setup

Follow these steps to enable DLS:

Click on the "gear" icon in the upper right corner of your screen or press "Escape".

Click on Options.

On the left side, click on Traffic Manager: President Edition.

Switch to the Gameplay tab.

Enable the Advanced Vehicle AI checkbox.

Move the Dynamic Lane Selection slider to the right.

Operating Principle

While the choice of to-be-used road Segments is given by the path-finding algorithm, DLS allows vehicles to re-evaluate their lane selection at every suitable Node during simulation time. A node is considered suitable if it facilitates the selection of at least two different target lanes on the next road segment. For each candidate lane, TM:PE's integrated traffic measurement engine supplies near-real-time traffic data which DLS uses to calculate a utility value of the respective lane. Based on this value and other factors, one of the candidate lanes is selected and the path is appropriately altered.

An in-depth process description is presented in the following subsections.

Selection of Candidate Lanes

As already mentioned above, precalculated choices of which segments to use remain untouched by DLS. In other words, if path-finding selects a certain stretch of road, the road is certainly going be used by the vehicle despite any possible adaptations made by DLS. However, for a given road segment that lies on the path, DLS is able to instruct vehicles to use lanes which have not formerly been selected by the path-finding algorithm.

While manipulating path data during simulation time, DLS guarantees that the vehicle is able to return to its precalculated path after at most four upcoming segments. To accomplish this, the first processing step runs a reachability analysis within a 5-segment window (4 upcoming segments plus the current segment). It discards lanes from consideration that are not connected with the original path by the fourth inspected segment. Reachability information is calculated by identifying transitive relationships within precalculated lane routing data ( see Vehicle routing → One-time calculations; transitive relationship: a lane X on the current segment is transitively connected with lane Z on the second next segment if a lane Y on the next segment exists that is connected with both lane X and with lane Z: ((X → Y) ∧ (Y → Z)) ⇒ (X → Z)).

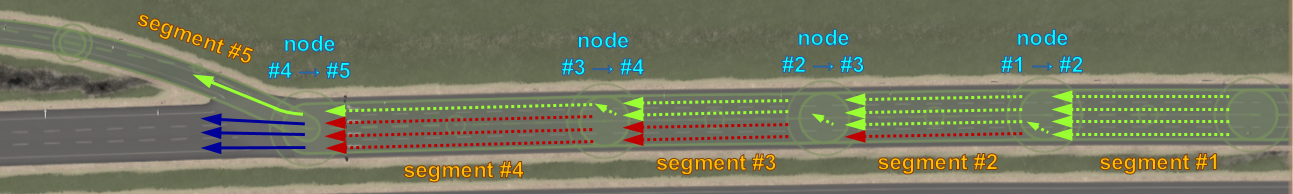

The image above shows a subset of all possible reachability analyses that are performed for vehicles heading for segment #5 (the highway ramp; highlighted with a solid green arrow), and originating from one of the available lanes of segment #1. In this example we assume that vehicles are allowed to switch lanes on highways only one-by-one (as with the Highway Junction Rules feature). For readability reasons, the first picture omits lane transitions that lead away from the ramp, though these are also considered by DLS. Green, dotted arrows indicate valid candidate lanes on upcoming segments, dark red, dotted arrows indicate invalid candidates. From the first image it can be concluded that every lane on segment #1 is a valid candidate such that vehicles on these lanes are able to reach segment #5, whereas starting from the leftmost lane of segment #2 it is not possible to reach segment #5, and so on. During simulation, a DLS-enabled vehicle moving on the 2nd rightmost lane of segment #3 would detect that only the rightmost lane of segment #4 finally leads to segment #5 and thus a lane change is necessary.

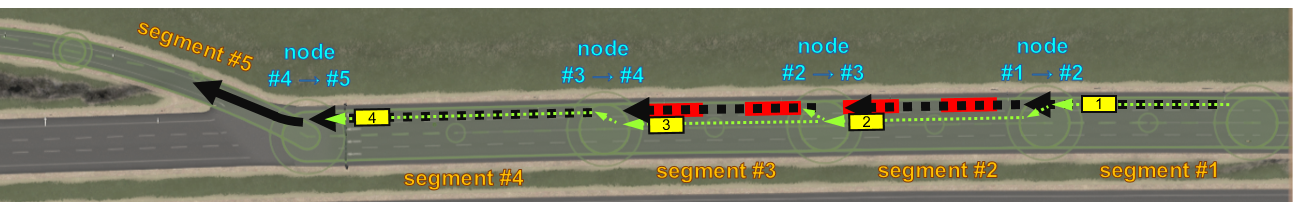

The second image shows a situation where a vehicle (yellow boxes; numbers indicate different points in time) deviates from its original path (original path: black, dotted arrows; DLS-modified path: green, dotted lines) such that at node #1 → #2 it switches one lane to the left (after the first DLS run), then decides to stays on this lane at node #2 → #3 (after the second DLS run) and finally switches back to the rightmost lane at node #3 → #4 (after the third DLS run where reachability analysis reveals that switching to the rightmost lane is the only valid action) in order to return to the original path. For example, this could have happened due to slow moving traffic on the rightmost lanes of segments #2 and #3. Note that at node #2 → #3 the vehicle has got two remaining options, either

staying on the lane or

switching to the rightmost lane.

After each reachability analysis, DLS evaluates the resulting set of valid lane transitions in order to determine which action to choose. The next subsections explain how actions are evaluated, compared and how decisions are produced.

Score calculation

After reachability analysis has identified a possible set of valid alternative lane transitions, DLS calculates scores for all lane transitions within the 5-segment window. The scoring function represents a trade-off between

(egoistic behavior) velocity maximization and

(altruistic behavior) overall traffic flow optimization.

During evaluation, lane transitions are categorized either as safe or as unsafe. Lane transitions are considered as safe if

using the candidate lane does not require a lane change or

no vehicles are approaching from behind.

The process of calculating final lane scores is described as follows:

The current cruise speed

vvcuris measured.The target cruise speed

vtrgis calculated, based onthe vehicle's maximum capable speed,

the set speed limit on the next lane,

if the vehicle is controlled by a Reckless Driver, and

randomization introduced by realistic speeds.

The current speed on the next lane

vlcuris measured.The difference between target cruise speed and measured speed on the next lane is calculated

(vtrgdiff = vlcur - vtrg).

For the calculated speed difference vtrgdiff holds:

vtrgdiff < 0if the vehicle would not be able to reach its target speed on the candidate lane, andvtrgdiff > 0if the vehicle would be able to reach its target speed.

Identifying appropriate actions

In terms of an egoistic point of view the first case (vtrgdiff < 0) is always suboptimal (since the vehicle is not able to maximize its velocity), whereas every lane that fulfills the second condition is of equal quality for an egoistic driver (since the vehicle would not be able to go faster even if the lane allowed faster driving). If DLS finds multiple safe lanes where the second condition (vtrgdiff > 0) holds it selects the one with the smallest (positive or zero) speed difference in order to promote altruistic behavior; in other words: In safe situations DLS-enabled vehicles tend to select lanes that allow for faster driving but favor lanes that are just as fast as required. If only suboptimal (safe) lanes can be identified vehicles tend to select the most optimal lane (even if it does not allow the vehicle to drive at its target speed).

In addition to the rules above,

(egoistic) speed gains and/or

(altruistic) traffic flow optimization

have to be significant (e.g. the vehicle must be able to drive at least 15% faster than before and/or expected speed loss must not exceed 10%) in order to trigger DLS-initiated lane changes.

In the case that only unsafe lane changes are identified (e.g. a fast vehicle approaches from behind or a traffic jam occurs) vehicles tend to stay on their lane if velocity differences between the current and other vehicles (vlcur - vvcur) exceed a certain threshold. In case that reachability analysis detects vanishing lane changing opportunities - e.g. like in the example above, where a highway exit comes close and the vehicle is required to switch lanes - some vehicles change lanes earlier, and a few will use the last possible lane changing point to switch back to the original path. The following table shows corresponding ratios:

Amount of vehicles | Number of segments in front of the last lane changing opportunity where vehicles will be forced to perform lane changes |

|---|---|

50.0% | 2 |

33.3% | 1 |

16.7% | 0 (last opportunity) |